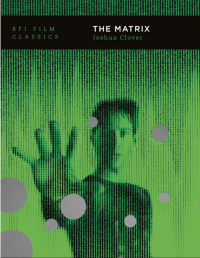

Stephen Hood joins us to discuss Matrix: Resurrections, Jeff Godsil gets to the bottom of Ben-Hur, Matthew of KBOO's Gremlin Time considers High Sierra, now out on the Criterion Collection, and in the book corner, a new edition of a monograph on The Matrix.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Matrix, Joshua Clover

By happy coincidence, the fourth, new Matrix movie is accompanied by the second edition of the British Film Institute's second edition of Joshua Clover’s monograph on the first film. Joshua Clover is a poet who once wrote for the Village Voice and now teachers at UC Davis. His book is one of the most insightful, detailed, and evocative critical studies I've read. It does all the things that you want a study to do, that is, to make connections, to make you see the movie anew, and in some cases, turn you around on film, and to be well-written.

One of the best ways to introduce his style is to hear his account of the film’s first few minutes, a scene in which Thomas Anderson is awoken from a nap and receives a handful of visitors picking up a mysterious disk, hidden in a copy of Jean Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulacrum:

“The entire scene howls with an excess of significance – especially during a second viewing. It opens with drowsing Neo awoken by his computer, and contacted for the first time by the rebels. This chat leads directly to a knock on the door (numbered 101, natch) from Neo’s client Choi, who, grateful to pay $2,000 for whatever’s on the disc, professes, ‘Hallelujah. You’re my saviour, man. My own personal Jesus Christ.’ Neo, curbing his friend’s enthusiasm, warns him, ‘You get caught using that ...’, to which Choi avers, ‘Yeah, I know. This never happened. You don’t exist.’ Moments later, he offers, ‘Hey, it just sounds to me like you need to unplug, man.’

“And so on, one oblivious double entendre after the next, through the Lewis Carroll moment when Neo follows the ‘white rabbit’ – a tattoo on the shoulder of Choi’s partner DuJour – down the hole of the plot.

“In the midst of all this referential mania, the most loaded image remains the disc in the gutted book. It reflects exactly Zizek’s inverted hierarchy, wherein the stark purity of binary code has replaced “even letters” in the depths of the irreal. The written word, that messy analog data-form, has been summarily discarded. Or, even more anxiously, the book form survives as nothing but a shell; it exists only to conceal a more powerful form of data, and to mask its own absence. The little invention is a perfect symbol for the procession of simulacra; we can see how such a set piece is, among other things, a seduction of theory.”

For this second edition, the author has gone through and changed the first names of the Wachowskis to accord with their new identities, and corrected a few typos, and in the back of the book he is added a new afterword taking an even more political look at the film. Part of it reads this:

“It is tempting to specify this further, to say that while the film begins from a depiction of cubicle labour, it reflects more particularly on its idealised audience within such a population: the information technology worker on whose skills the film’s visuals depend and whose tastes it is designed to flatter with its videogame stylings and hacker-loving narrative. Matrix = Marx + IT, that is in some regard the entirety of the book. But I think that is too narrow. While the growing cadre of tech workers surely occupied more and more office space in and around 1999, the underlying transformation in the job market was a broader phenomenon. About a century previous, the United States had come the closest in its history to an even distribution among sectors, with agriculture, industry and services all between 30 and 40 per cent. By the time of the release of The Matrix, agricultural labour was fading toward nil, industrial labour accounted for less than a quarter of all workers, while services now employed more than 70 per cent. Not all of these were office workers, but enough that (as of 2013) ‘office and administrative support’ was the largest subcategory of employment, more than ‘sales’, more than ‘food preparation and serving’. The nation had come quite a distance from The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

“What does it mean and how does it feel to live in a society, an economy, an individual life dominated by service work, to have the hours of your life shaped by the particular form of such labour that takes place in an office, an office where you are almost certainly not a budding star coder headed for the ownership class with your payment in shares of a rocketing startup, but more likely an underpaid data entry drone, trapped in a cubicle, giving yourself up bit by bit to some corporation just so you can live, captive to a fantastic view of that situation that you cling to just make such a life bearable, a view of reality so transfigured as to be stood on its head but in its distortions and empty seductions necessary just to make it through the week? That question is I think the heart of The Matrix. And it has only become more pressing over time.”

Now that there is suddenly upon us a new Matrix film, Joshua Clover's book serves as an ideal companion to the film and its self referentiality.

- KBOO