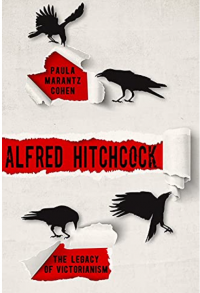

Alfred Hitchcock is a filmmaker whose work yields so many ideas, observations, and lessons in filmmaking. This week Jeff Godsil revisits his war film Foreign Correspondent, while Matthew of KB00's Gremlin Time looks at his experiment with 3-D in the thriller Dial "M" for Murder, while in the book corner, we survey a volume on the legacy of Victorianism and the breakthrough of modernism in Hitchcock's career. The text of the review is below.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––-

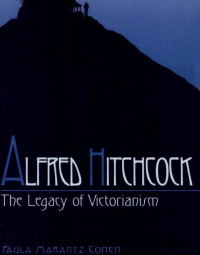

When the University Press of Kentucky press first published Alfred Hitchcock: The Legacy of Victorianism, in 1995, there was yet to be an internet, yet no wide use of home computers, there were going to be three or more wars, DVDs which expanded the viewership of Hitchcock’s films, and probably several hundred more books on the director.

But almost 30 years of these changes and critical studies have brought little change to the author’s essential points.

Professor Paula Marantz Cohen, of Drexel, has one big idea and then in essays about individual films, and a great many little insights. The big idea is that the In gross brevity, Hitchcock strove to militate the male cinema world with some of the principals of the novel, with its detailed relationships, and attentions to feelings and character subjectivity.

The title is misleading, giving the reader the idea that the volume might be an elucidation of a musty Hitchcockian world of lace doilies, rigorously attended tea times, gas lamps, street urchins, contested wills, and corpses lying in fog-blanketed alleys, as ineffective bobbies bark directions in cockney accents. But the “legacy has less to do with socio-cultural emblems than with the change in popular culture from woman-oriented fiction from the 1800s on, to the creation of cinema, a “masculinist” form that did not explore feelings, relationships, and personality to the extent of the popular novel.

The bulk of novels were written and read by women, and then men such as Hardy and Conrd wrote but chaffed against the restrictions that female readership or impede by publishers imposed on the genre. Movies on the other hand, were produced and created mostly by men (though women were a significant part of film production in the early years), and they appealed to boys and men with comedies and action stories and little in the way of self-reflection.

Professor Cohen examines about 18 films of Hitchcock in detail in 10 chapters: Rebecca, Sabotage, Psychoanalysis versus Surrealism: Spellbound, Father-Daughter Plots in Shadow of a Doubt, Stage Fright, Strangers on a Train, then Rope, I Confess, The Daughter’s Effect in Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Wrong Man, Vertigo, The Emergence of Mother in Psycho, Beyond the Family Nexus in a general “defense” of late films such as Topaz, Frenzy, and Family Plot, and finally some thoughts on the impact of the weekly Alfred Hitchcock TV show.

Professor Cohen discusses not just famous works but also widely selected films. Chapter three looks at Spellbound. There is little critical work on this film aside from a brilliant essay by Tom Hyde in the film journal Cinemonkey, and the range of her references are evident as I share a long, edited excerpt from that chapter.

"Spellbound (along with Shadow of a Doubt) marks the beginning of Hitchcock’s unencumbered drive to reclaim for cinematic use a novelistic concept of character.

"During the period of actual production, Hitchcock managed to assert far more autonomy than he had on Rebecca.

"Although Spellbound is far from an unmitigated success, without Selznick it could have been far worse. Indeed, it seems clear that Selznick made valuable contributions not only to Rebecca and Spellbound but also to Hitchcock’s development as a filmmaker. His contribution can be summarized as follows: he steered Hitchcock toward strong domestic narratives (the du Maurier novel; the psychoanalytic theme); he alerted Hitchcock to the challenge of novelistic character (by forcing him to be faithful to the novel in the making of Rebecca; by assigning Mary Romm and Ben Hecht to the scripting of Spellbound); and he encouraged Hitchcock in a more creative use of the female performer (by suggesting more close-ups of Joan Fontaine in Rebecca; by the felicitous casting of Ingrid Bergman in Spellbound).

"Psychoanalysis was dubbed the talking cure when Freud realized that he could leave off hypnotizing his patients and let them use free-associative talk to produce clues to the source of their symptoms. Talk, as Freud used it, was a therapeutic method by which unconscious information could be brought to the surface and made available for interpretation. In the gaps and patterns produced by talk, the therapist could help the patient piece together a repressed story and, in so doing, effect a cure. In this respect, psychoanalysis has much in common with novel-writing, and it is no coincidence that it appeared as a science at the time when the novel figured most prominently in Western culture. Novels, as they developed as a genre, moved from being vehicles for plot contrivance in the picaresque adventure stories of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to being vehicles for character elaboration in the nineteenth century. In short, this was a shift in the nature of story: from a record of happenings to a revelation about mind and heart.

'The surrealist movement which florished briefly in Paris in the 1920s was an attempt to build artistically on the insights produced by psychoanalysis but, at the same time, to break with the drive for rational coherence for narrative that psychoanalysis posited as its goal. Where psychoanalysis filtered the incoherent talk of patients through the mediator of the therapist to produce a story that explained the patient, surrealism sought to reproduce the sense of surprise and incoherence that the mind presents before such consolidation.

"As an expressive medium, literature was not well suited to the surrealist agenda. This was because the reader, accustomed to viewing written words within the context of a conventional narrative sequence, was always falling into the trap of imposing such a narrative, even when it was not intended.

"As for the medium of film (despite such surrealist classics as Blood of a Poet and Un Chien Andalou), it was too costly and dependent on a large market to be a major outlet for surrealist expression. Because film had early on taken what Christian Metz has termed the narrative road, it also represented an obstacle to surrealism’s anti-narrative drive. Pictorial art had none of these draw-backs. Painting was a relatively cheap and convenient mode of artistic expression and had the further advantage of not bearing the weight of narrative associations. Surrealist painters took the symbols and images that psychoanalysis had gathered from dreams and free association material that psychological novels and psychoanalytic case histories had narratized to present a coherent self and scattered these about their canvases to produce a new kind of landscape.

"Psychoanalysis places special emphasis on the woman as unusually sensitive to emotional experience. Many theorists, of course, have noted the sexist premise of this assumption: that the male psychiatrist (Freud being the paternal precursor) uses the female psyche as the ground for interpretation and theory building. Yet because analytic talk presumes a narrative that can be circulated and learned, there is also a sense in which psychoanalysis provides women with the tools for self-analysis. The most innovative novels were written by men, but in schooling women in a complicated subjectivity, they eventually became associated with female power and threatened the patriarchal institutions and values they were designed to support. Women became novelists in great numbers, and they also became psychoanalysts. Freud himself included a number of women in his inner circle. The paradox of women’s relationship to psychoanalysis is articulated in Spellbound by Ingrid Bergman’s character Constance Peterson’s mentor, the Freud-like Dr. Brulov, whose combined indulgence and dismissal of his former student embodies the attitude of the Victorian father toward his daughter. Women make the best psychoanalysts till they fall in love, he tells her, then they make the best patients. When Constance starts talking about her love for John, Brulov tells her to stop speaking baby talk, the opposite of professional analytic talk but precisely what a psychoanalyst wants a patient to talk in order to gain access to the secrets of the unconscious.

"The confusion that psychoanalytic narrative introduces in the positioning of the female subject (Is she the subject of analysis or the subject doing the analysis, or both?) disappears in surrealist art. The surrealist movement was entirely dominated by men (though a number of women “circulated†in the group as sexual objects, a practice that occurs, significantly, in Rope). When the female figure appears in surrealist paintings it tends to be represented in odd and distorted ways, often in pieces, as an objectified motif of sexuality. This can be attributed in part to the backlash against that feminization associated with Victorian culture.

"In the context of psychoanalytic and surrealist ideas, early entertainment film was a new kind of hybrid that tied together the strands of narrative and pictorial traditions. It associated itself with a world of visual surfaces, and yet it used narrative to tell a story. As Metz put it, there was a demand for narrative; the Lumiere brothers slice-of-life films had failed to attract.

"Spellbound is a turning point because it is the first film in which Hitchcock grapples directly with the paradox of how to render interiority in a medium oriented toward surfaces. He takes a storyline that employs psychoanalysis as a theme and seeks to find visual correlatives for the psychoanalytic narrative. This explains his decision to employ Salvador Dali to create a representation of the protagonist’s dream.20

"I would argue that the effect in Spellbound is less successful because the moral ambiguity that the flashback leaves in its wake is less assimilatable to the notion of male character than it is to the notion of female character. The problem, in other words, is less a function of Gregory Peck’s acting than of the contradiction posed by the script between a highly charged psychological experience, rendered graphically and requiring a complex self to support it, and the need for the kind of simple innocence that the script requires of its protagonist (and of men in general) with respect to the working out of plot. This contradiction can be said to arise out of an ideological need to understand male aggression as simple and accidental rather than as complex and conditioned, and thereby to separate the heroically constructive results of male action from the disturbingly destructive. The problem with both the childhood flashback and the dream sequence connects directly with the problem they are meant to eludicate that of male character as a locus for subjectivity.

"Spellbound is an ambitious film because it tries to produce a male character of emotional and psychological complexity. It fails in this because the idea of male depth is incompatible with the ethos of classical narrative film, which relies on the active hero to propel the plot and engage the active participation of the viewer in its resolution. John Ballantine functions in the film as a mystery to be solved, and attempts at visual evocativeness regarding his character seem to get in the way of the narrative drive to unravel that mystery and to make it fall neatly within the whodunit plot."

In its representation of the male and female subject, Spellbound is an experimental work: awkward, overwrought, and just plain silly in places. Yet it is tremendously rich in technical and conceptual possibilities. The film’s central weakness its inability to make the male subject the center of a psychological plot would be readdressed in later films. After Spellbound, Hitchcock’s plots increasingly turn upon the ways in which men are tantalized and tortured by a subjective experience associated with women.

- KBOO