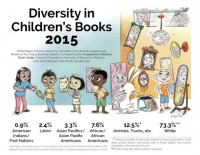

Cecil & Celeste are joined by Kirby McCurtis to discuss the images our children consume in pop culture and where those images come from. What are the modern alternatives to these established and harmful depictions? The diversity gap in children's publishing is overwhelming but groups like thebrownbookshelf.com are trying to highlight the alternatives and promote the voices of Black and Brown authors and artists.

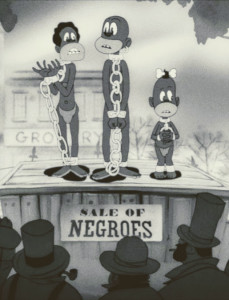

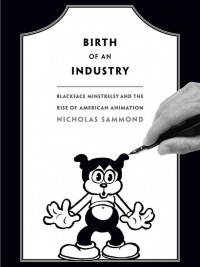

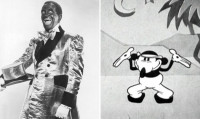

In Birth of an Industry, Nicholas Sammond describes how popular early American cartoon characters were derived from blackface minstrelsy. He charts the industrialization of animation in the early twentieth century, its representation in the cartoons themselves, and how important blackface minstrels were to that performance, standing in for the frustrations of animation workers. Cherished cartoon characters, such as Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, were conceived and developed using blackface minstrelsy's visual and performative conventions: these characters are not like minstrels; they are minstrels. They play out the social, cultural, political, and racial anxieties and desires that link race to the laboring body, just as live minstrel show performers did. Carefully examining how early animation helped to naturalize virulent racial formations, Sammond explores how cartoons used laughter and sentimentality to make those stereotypes seem not only less cruel, but actually pleasurable. Although the visible links between cartoon characters and the minstrel stage faded long ago, Sammond shows how important those links are to thinking about animation then and now, and about how cartoons continue to help to illuminate the central place of race in American cultural and social life.

from Nimah Timmons:

Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation looks at the early history of animation, from the 1910s to mid-1930s, and its genealogical relationship with the practice of minstrelsy. For Sammond, early animation characters, such as Koko the Clown, Felix the Cat, and Mickey Mouse, were new forms of representing the practice of minstrelsy. Sammond writes of these new minstrels, “Trademark cartoon characters such as Mickey were becoming vestigial minstrels, carrying all (or many) of the markers of minstrelsy while rarely referring to the tradition itself”. Such characteristics included the characters being drawn as black, the inclusion of white gloves, and a mischievous personality that typically acts counter to their creators. What is intriguing about Sammond’s approach to the subject is that he does not limit himself to simply understanding the representational practice of these minstrels; he also incorporates the production and labor that went into creating them. Sammond organizes the text into sections regarding performance, labor, space and race (placed in this respective order). By structuring the text in this way, Sammond intends to locate the multiple factors he believes play into the production of minstrelsy animation. The production of these representations for Sammond are dependent on the transformation of labor and presence of the animator(s). In the chapter on space, Sammond begins to work through the transfer of sound spaces. This follows the historical progression of animation from the silent era to the use of sound. In the final chapter, the emphasis is placed upon the ways in which Blackness is displayed, particularly in reference to the later historical period of the study. Although each chapter is dedicated toward a theme of the animation practice, these discussions on performance and representations are seen throughout the text. Sammond makes the point numerous times that the assembly line style of animation led animators to create characters with minstrel characteristics. He notes that in the 1910s, animation practice focused on the individualized relationship between the animators 200 Book Reviews and their creations. This allowed for an animation practice that mimicked the performances seen in minstrel performances. However, by the 1930s, animation turned towards the Fordist Model that minimized the individualistic characteristic of previous animation. For animators, their characters, who already had embedded minstrel characteristics, become the voice for their frustrations in their new work environments. At the same time, the text represents not only the historical narrative of racist performance traditions, but also the mass production and distribution of racist representations. Towards the closing of the text, Sammond decides to look at the representational legacy of blackface, providing an analysis of cotemporaneous film that utilizes blackface. Most notably is a case study on the film Tropic Thunder. Sammond’s work in The Birth of An Industry is notable and fascinating. His discussion weaving in both production and representational practices reveals far more than an analysis on either form individually. By unpacking each component of the production and representation of minstrel animation, Sammond builds the space needed for an insightful discussion.

- KBOO