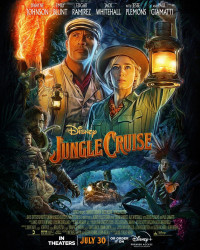

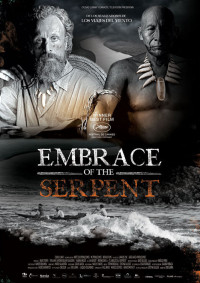

Today we take a look at the Criterion Collection publication of Johnnie To's Throw Down, while Jeff Godsil ponders Luis Buñuel's Belle du jour, and Matthew of KBOO's Gremlin Time compares the recent Disney movie Jungle Cruise to the earlier 2015 film from Colombia, Embrace of the Serpent, and in the book corner, is the second edition of the BFI monograph on Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood, an adaptation of Macbeth.

Throne of Blood

It’s arguable that the best type of film is the kind that falls under the general rubric of existential humanism. This term covered films as diverse as the Italian Neo-realists, but also the religious-inflected Bergman of Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal, and various Eastern European films of the ‘60s. But arguably the best practitioner was Akira Kurosawa, whose string of masterpieces from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s, from Roshomon to High and Low and beyond, and especially Ikiru, defined the searching and striving of this type of film.

What is the point of life? What can one person do in a seemingly indifferent universe? Kurosawa raised variations on these questions for almost 20 years, while often drawing on western writers such as Doestoyefsky to do so. Among them was Shakespeare, and Kurosawa’s adaptation of the playwright’s most concise and pointed play also becomes Kurosawa’s most concise treatment of his themes.

One of the unstated facets of Throne of Blood is that it is one of the great “king goes nuts” films, as the Macbeth here, Washizu, is turned against by his soldiers and chased by waves of arrows. Other films along these lines include István Szabó’s Colonel Redl, various versions of Richard III, De Palma’s Scarface, and the Bruno Ganz Hitler drama Der Untergang, or Downfall. Such concluding sequences are great opportunities for over-acting.

Now the second edition of a British Film Institute monograph on Kurosawa’s film from 1957 illuminates just how dense and visually realized is Throne of Blood (in Japanese the title translates as Spider-web Castle). Author Robert N. Watson is a Shakespeare specialist but you’d think he was also a film scholar from the way he summarizes Throne of Blood as a cinematic experience, tracing visual motifs from blocking and the positioning of bodies, foreground versus background, and the use of verticals to comment on situations. As he walks the reader through the film, he notes the manner in which Kurosawa creates visual versions of the narrative or poetic equivalents in the original play.

This second edition of the book, originally published in 2xxx, includes a new forward that reminds the reader of Watson’s differences from other writers on the film, and offers an update on the film’s status in cinema history.

The best way to give the flavor of this beautifully written and insightful book is to quote the ending, where he compares the advance of Birnam Wood in play and film:

“Both versions reveal a more literal, pragmatic level behind the seeming supernatural signal of the moving forest: we will eventually hear that the trees were brought to provide the advancing army with camouflage and protection against arrows from the castle.

But there may be an even simpler, more fundamentally material level behind that one. Untold ages ago, land was cleared for human habitation and agriculture, as we reshaped the world to suit and serve our needs. In Scotland, shipbuilding caused extensive deforestation during the reign of the historical Macbeth, and the initiation of iron-smelting rapidly accelerated that process at the time Shakespeare was writing the play.

Someday, erosion and gravity will erase all our structures, and wild vegetation will reclaim all that land. So the [narrative framing devices] of Throne of Blood constitute a lesson for the human race, conveyed by something like deep-time-lapse photography.

It is a lesson that could bring us some peace, in a Zen Buddhist mode, but at the price of a kind of humility that does not come to us easily.

Kurosawa places no blackout or wipe between the final view of the forest advancing and the renewed view of the castle consumed by dust and fog. That encroaching wilderness is a bridge to the lesson of the film’s opening sequence, all part of the same meaningless story, the same bad joke on human ambition, though it leaves a kind of beautifully bleak majesty in its wake. All that is left is the marker telling this story – a story of what is inevitably and forever gone: ‘Here stood Spider’s Web Castle’. We share in the futility: having reached the point where Washizu’s story ends, we are back where we started. Fade out. The end.

It seems like an irrefutable and insurmountable truth. But people have never gone to Throne of Blood hoping to stare at an ink-painting of Mount Fuji for two hours. What happens between the beginning and the end of a film, or a life, or a species, or a universe – degrees of quality, beauty, pleasure, trust, affection, energy and meaning – still matters. Like the makers of many film classics, Kurosawa is enough of a traditional humanistic artist that he sends his audiences out of the movie theatre determined to live better.”

————————————————

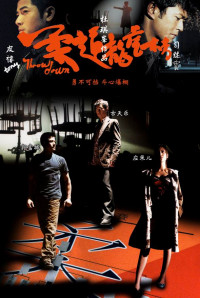

Throw Down

Given that Johnny To, or, as he is known elsewhere in the world, Johnnie To Kei Fung, has made 72 movies so far, it might seem odd the Criterion Collection chose for its debut Johnny To film Throw Down, a romantic friendship comedy-drama that can be a challenge to western viewers.

Yet it turns out the film is not only Johnny To’s favorite among his own work, but it has distinct links to Akira Kurosawa, both as the dedicatee of the film and the inspiration for the movie’s philosophical character trajectory.

Set in a Hong Kong of neon signs, chiaroscuro nightclubs, and packed gambling parlors, Throw Down is a character study of three friends—a former judo champion who is now a bar-owning alcoholic gambling addict (Louis Koo) – his bar is called After Hours, after Scorsese’s film – along with an aspiring judo champion (Aaron Kwok), and an ambitious singer (Cherrie Ying). Throw Down specifically cites Kurosawa’s debut feature, Sanshiro Sugata as an influence, but To’s film blends comedy, fight scenes, and heart-breaking sentimental in a tale about the redemptive power of friendship. That theme is beautifully realized in a seemingly irrelevant side moment when the three of them work together one night to free a red balloon trapped under a tree.

Sanshiro Sugata was Kurosawa’s first feature and traced the path to humility of a naturally talented judo student. It’s an impressive debut, followed a few years later by an irrelevant sequel. It’s also surprising to learn that the movie as we have it is missing some 20 minutes, cut between its original release in the ‘40s and re-release in the early ‘50s, but not due to censorship, and the footage has not yet been recovered. Yet the interested viewer can track down the contents. For one thing, there is a copy of the screenplay available in volume two of a difficult-to-find set of scripts published in the early-1970s, and for another the film was also re-made in the 1960s, produced by Kurosawa and based on the two Sugata screenplays. From these we can see that some crucial moments of exposition and motivation are now missing, and for lovers of Kurosawa, it’s well-worth tracking down at least the re-make. [Only five or six volumes in The Complete Works of Akira Kurosawa were published, according to later editions of Donald Richie’s The Films of Akira Kurosawa.]

But back to Throw Down: Perhaps it’s best to quote Stephen Teo in his book on Johnny To, Director in Action from Hong Kong University Press

“Recognition of Throw Down as To’s greatest film may only come in time, as To himself is probably aware. Throw Down is very much a retrospective movie, not so much because it looks back to Kurosawa but because it looks back on itself. One can appreciate its individual greatness only after multiple viewings whereas a first viewing might very well leave the viewer dumbfounded, whereby the conclusion would be that the film is a failure. It is not that by any means. To has made an inductive masterpiece with a lot of heart but without much sentimentality so that the viewer is forced to search for cause and affect — the connections between action and emotion. In short, To has expressed an intellectual response to crisis and action — the prevalent tone of his exercises.”

The Criterion disc, No. 1, 092, is a 4K digital restoration, with 5.1 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack on the Blu-ray, which highlights the great music and soundtrack so characteristic of To’s films.

There is also an interview from 2004 with To, a making-of documentary featuring To and actors Louis Koo, Aaron Kwok, Cherrie Ying, and Tony Leung Ka-fai, new interviews with co-screenwriter Yau Nai-hoi, composer Peter Kam, and film scholars David Bordwell, who explains, helpfully, To’s narrative strategies, and Caroline Guo, who contextualizes Throw Down within Hong Kong commercial cinema. Finally there is the film’s trailer, new subtitles, and in the booklet, an essay by Sean Gilman who expands on the Kurosawa connection.

Throw Down is a revelation within Johnnie To’s career and is a funny and touching experience.

- KBOO