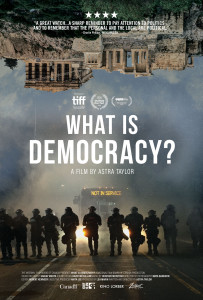

For the Old Mole 3/18/19

Jan: What is Democracy? directed by philosopher filmmaker and activist Astra Taylor answers the question in the film's title through an expository style, an approach to documentary that uses interviews and images to build an argument. The argument advanced in the film is that most Western countries are being run by a really bad form of democracy. Taylor travels the world meeting thinkers, activists, and philosophers who are troubled by the way democracy operates in their societies. She returns periodically to two main pillars of the film: group discussions at the original sites of democracy in Athens and a large Italian mural depicting how democracy works, explained to us by Marxist scholar Silvia Federici. The mural then becomes a touchstone of the film in foregrounding financial oligarchs dominating the ideology and practices of governance in much of the modern world. Many of us learned in school that we owe a lot to the Greeks in medicine, law, moral philosophy, and governance, and clearly Astra Taylor thinks we have something to learn from the Greeks. What do you think we owe to the Greeks? And what do you think she's saying here in reaching back to this classical era.

Frann: I think we see a lot of things come out from that touchstone of the Greeks. Clearly Plato's idea of the king, the philosopher-king is not something that we necessarily want to embrace. But there are a number of things that do come out; one is just the idea that government should be about making a good life and ensuring the well-being of a polis, of a people, of a society, and then the question becomes who counts as part of that Society who's in who's out and that gets addressed in various ways in the film. But there are a number of other things that come up. One is this idea of moving people into different areas of the city so that the groupings would not be just based on friendship, but on proximity and the possibility of engaging with people who are not like you—that democracy requires a broader conception than just you or your friends and your personal relations-- that it has to in some sense be about general well-being, not just your own interest.

Jan: And that's still a very radical idea that is far from realized in the world, that we have obligations to others beyond our friends or family in-group-- to represent people we don't know— that we all share some common interest, the idea of universal rights. It seemed to me the the idea was not not to pull out the best model of governance from the Greeks but to demonstrate that flowering of ideas around democracy: this idea that it’s always contested, that there's a debate and that there are competing models and that this is more than deciding on a model. There is a discussion that's kind of new for this country about What is socialism? What is democratic socialism? Can we have any meaningful democracy under capitalism and more than the answer It's that there is a discussion, debate around it.

Frann: I'm not sure that that's entirely new for America. There's been a strong socialist tradition in America; back before the Cold War there were lots of American socialists, but that is a tradition that we’ve forgotten. It's not something that the film addresses, but it does address various forms of democracy that extend beyond the notion of representative government which is the more limited picture that that we often get in school lessons and so on. There are some some great moments where she interviews school children talking whether their school is run democratically: Do you have a say? and the notion of extending democracy beyond going and voting every four years or every two years or whatever. Having a say in your workplace, having a say in your school, having a say in your daily life, having a say in your personal life— the idea that democracy is something that needs to extend throughout life, that all of life is political in that sense, is something that comes out in some of those conversations that I think is valuable.

Jan: I think the claim that of course is so much associated with feminism, that the political is personal, that extends into how families are organized and run, how communities are organized. The question was posed but overall it seems that the film was more invested in exposing the hypocrisies in the false promises of democracy under capitalism and how it's a cover for a small group of elites excluding others and running things. And I think there is a long history to of of democratic experiments and fights over claims made on the state and on forms of governance, claims made in the name of democracy for having more democratic child-rearing practices, that you cannot dominate people or exploit people in the context of personal life, work, play, struggle. So I felt this was a limitation of the film, in not acknowledging some of the history of fights that have been won, gains that have made the society better.

Frann: Maybe it was in the interviews with Cornel West or in some of the statements --There's a speech by Angela Davis in the film that we see clips from-- there's discussion of this notion that democracy has never in the United States or, or anywhere, has never been democracy for everybody, but that the United States is founded on indigenous genocide, that it is founded on slavery. It begins with all of this talk of Liberty and freedom that does not include everybody—it doesn't include women. It doesn't include enslaved people. It doesn't initially include people who don't own property. There are a lot of limitations there and I think the film does stress the way is that economic inequality really runs counter to the possibility of political democracy--rule by the people-- of people's empowerment.

Jan: But yet early on in the film Cornel West poses this problem that I think is kind of set aside, that majority rule, forms of democracy from below, always have the potential for tyranny, and he even says for fascism, that there have been fascist regimes that have been elected democratically. And we see a lot of mass street protests and demonstrations, but how all of the uprisings from below translate into a democratically-run society is...I think the film is facil on that front, how you get from here to there.

Frann: Cornel West mentions that for instance Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which was a democratizing move was not a democratic move, right? It was in a presidential Proclamation. The Supreme Court's Brown versus Board of Education decision was not Democratic. It was made by the Supreme Court, which is this tiny body of people who are there for life. And so those are not Democratic decisions, but they broaden the possibilities for democracy. He doesn't talk about at least I don't recall him talking in this film about the fact that both of those are responses in part at least to mass movements. There was a huge Abolitionist Movement prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. There was a huge Civil Rights Movement prior to the Brown versus Board of Education decision. So those are things that are coming in response to mass democratic movement.

Jan: And I think victories need to be acknowledged and celebrated as well as critiqued.

Frann: Silvia Federici talks about the idea that the feminist movement has really made a really important theoretical accomplishment in stressing that the personal is political and that the domestic sphere is not outside of the political sphere. So, I mean, I think there's sort of an acknowledgments of that.

Jan: Perhaps it’s Wendy Brown who brings in this idea too that we have to think about democracy as not only the freedom to be left alone, which is kind of an American hyper individualistic driven notion of a democracy— being able to do what you want unbothered by the government –versus the Democracy as being in relation to others, as understanding our common interest, depends on the welfare of others, and that was introduced but not very developed in the film, that distinction.

Frann: I think when she talks to the refugees and the people around the the refugee camp in Piraeus in Greece about the idea of what they want, freedom or democracy? What do they want? What does it mean to them? And it includes safety or it starts with safety and Justice that mean people who are fleeing from violence and from unlivable situations are not in a position to debate the fine points of government structures. They want a safe place to live. They don't be shot in their beds. They don't want to be raped as they're crossing the border. They want to be able to have stable lives.

Jan: I think that the passage with refugees seemed limited to me as it was framed; it's not just about freely freedom to migrate but freedom to stay and freedom to live in and the fact that you happen to be born in a country why that gives people here anymore rights anywhere else should be questioned. So it felt like a film kind of touched on some of these bigger problems and maybe a burden of any project of the scope of a film like this.

Frann: if you're going from ancient Greece to the present day, you're covering a lot of territory.

Jan: Maybe the important point is challenging notions of democracy and how you can have different forms of it. But for example in Cuba since the revolution there has been impressive local democratic practices, but also very authoritarian government. And so you have these mixed experiments and I think some of that that localism local co-ops and that sort of thing are highlighted in the film without looking at some of the problems in coordinating them within the system of the state.

Frann: One of the places that she interviews some people-- and I'm not sure how clear it is in the film, but the trauma doctors she talks to in Greece are working at an autonomous Clinic that during the Greek debt crisis and the whole betrayal of Syriza in not following through on the referendum in Greece, the economic situation there was terrible and so there were a lot of autonomous clinics set up to pick up the slack that was dropped by the government which was stretched by the EU and the German bankers and those are great but they're also things that really put pressure on for instance the doctors who are working pro bono in those clinics on top of their other jobs if they still have other jobs. They were alternatives to the state that worked very well in that context, but do not mean that people don't have the right to make claims on the state and we should be able to make claims on the state.

Jan: And maybe there's a similar dilemma around the Occupy Movement. And this also was incredible experiment in local democracy and taking over public spaces and providing Healthcare care for people but how you sustain these experiments and democracy over time is another matter.

Frann: One of the closing moments is Silvia Federici saying, you know democracy is worth fighting for but you always have to be very careful about what you mean by democracy because it's a term that gets appropriated in lots of ways for lots of ends that we would not necessarily call Democratic—but it's always worth fighting for democracy from below, not from above.

Jan: And I think this basic idea that I still think is worthy of acknowledging, with origins in Greek philosophy, that we we have an obligation to understand and represent and share in the interest of people beyond our kinship group, beyond people we know and it's still a very big problem in the world.

Frann: There's a group of activists in Miami talking about their experience. A lot of them are immigrants or children of immigrants from the Caribbean and Latin America andone of them talks about the ways that people don't necessarily realize that understanding the experiences of people in different groups is important and that what we all need to do is, you know, that the African-American needs to understand the Cuban-American situation and the Nicaraguan needs to understand the Costa Rican and so on; that people need to draw on the different kinds of experiences and situations and histories that come from different places in order to build something better, in order to keep working for something better.

Jan: And that it's a more satisfying and fulfilling and larger life that also require something of us. Maybe education in the sense and then the form a limited sense, but maybe a broader notion of learning how to be together across differences and how to understand different points of view. That's part of what's known as a democratic multi-tenancy organization that no one group has the line on things.

Frann: There's one point where Astra Taylor asks, You know to what extent, it seems like democracy requires education. It requires intellectual engagement, that it's really demanding something of people; and then we moved from there. I think that's where we move to talking with some of the students in the US, and she askes them about whether their school is democratic and of course, it's not at all; their needs are not being met; they don't have a say in what's going on; and that when they learn about democracy in class, It’s just about government and checks and balances or something like that, Right? that it's not it's not understood in a living way as something that occupies all of people's lives, but that it should be understood as something that is part of everyday life, that we need to claim a notion of democracy in the workplace, in the schoolplace and not just going in and voting or whatever.

Jan: So all of the teachers strikes and the teachers fighting for a schools as places of Refuge places where those without papers can get an education where their kids can see a nurse get Healthcare if they need to--

Frann: or food

Jan: or food... I find hope in teachers being so much in the lead now. And so it's not just access to college or access to higher education. But this more radical notion of schools as public places and places for experiments in democracy.

Jan: So the film is What is Democracy?, a question that remains a question for you to discuss among yourselves. It’s playing two nights this week at the Portland International Film Festival.

Frann: Wednesday and Thursday, March 20th and 21st. And the director Astra Taylor will be there both nights for Q&A. So you can ask her about some of these things and engage in debate.

Jan: This has been Jan Haaken and Frann Michel talking today about the documentary film, What is Democracy?

Transcript made with the assistance of Vocalmatic.

- KBOO